What Are the 5 Stages of Palliative Care? 2026 Update

Text to speech

Duration: 00:00

Font size

Published: 19 Feb, 2026

Share this on:

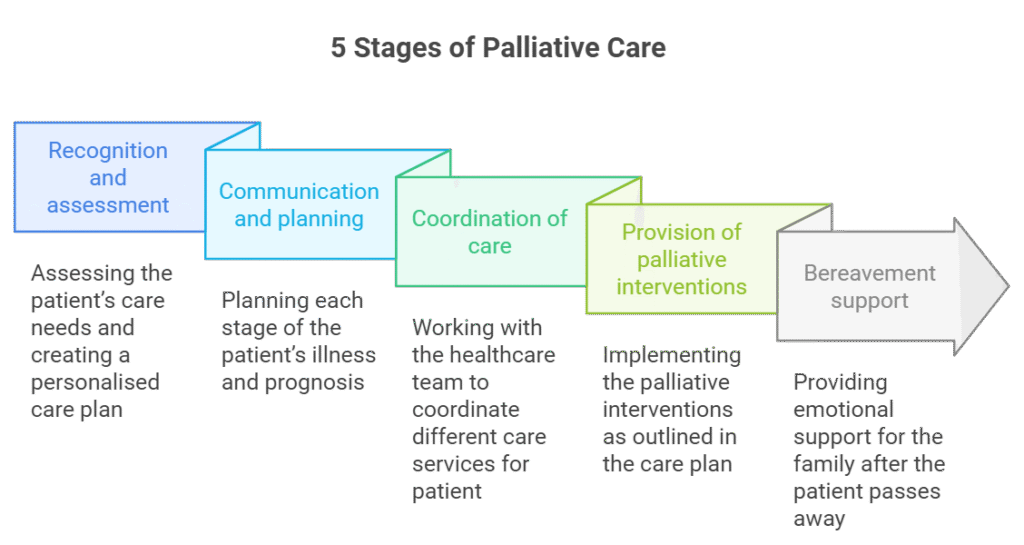

The 5 stages of palliative care provide a practical framework that helps families and care teams support someone living with a serious or terminal condition. While the NHS does not publish an official “5 stages of palliative care NHS” model, many professionals use this five-part structure to organise care around comfort, dignity, and quality of life.

The five stages typically include:

- Creating a personalised care plan

- Early symptom management and practical support

- Emotional, spiritual, and psychological support

- End-of-life (terminal) care

- Bereavement support for family and loved ones

These stages do not follow a strict timeline. Care teams adapt them to the person’s needs, which may change quickly or gradually depending on the illness.

Understanding this framework helps caregivers prepare for what lies ahead. It also makes difficult conversations, about comfort, treatment choices, and future planning, clearer and more manageable.

Does Palliative Care Mean Death?

Many families ask this quietly: Does palliative care mean death?

No. Palliative care does not mean someone is about to die.

Doctors introduce palliative care when a person has a serious or life-limiting illness. The goal is to improve comfort, manage symptoms, and protect quality of life, whether that person lives for months or many years.

People often confuse end of life care vs palliative care, but they are not the same:

- Palliative care can begin at diagnosis and run alongside treatments such as chemotherapy, dialysis, or heart medication.

- End-of-life care usually refers to care in the final year of life, when the focus shifts fully toward comfort rather than cure.

You may also see terms like terminal condition, terminal care, or dying pathway. Healthcare teams use these words when an illness no longer responds to treatment and life expectancy becomes limited. Even then, palliative care does not “cause” death; it supports comfort and dignity as the illness progresses.

Some people search online for phrases like “why palliative care is bad.” This fear often comes from misunderstanding. Families sometimes worry that starting palliative care means “giving up.” In reality, early palliative care often improves symptom control, reduces hospital admissions, and gives patients more control over their decisions.

The real question isn’t whether palliative care means death.

The better question is: How can we make this time as comfortable, meaningful, and supported as possible?

That is what palliative care aims to answer.

RELATED: Who Is a Care Assistant? 2026 Salaries, Duties, Responsibilities

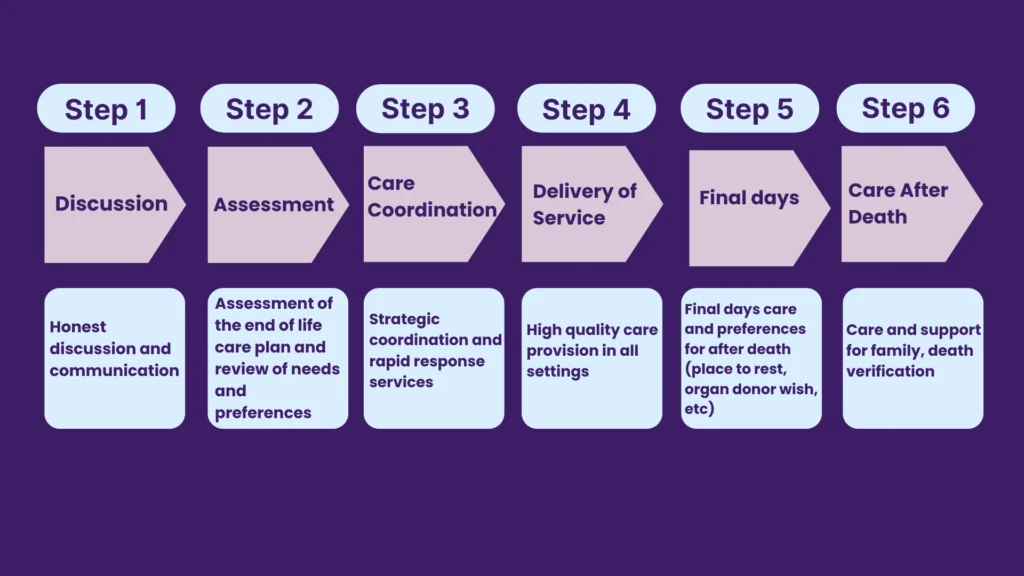

When Do the Palliative Care Stages of Dying Begin?

Many caregivers wonder when the palliative care stages of dying actually begin.

Palliative care can start at any point after a serious diagnosis. Doctors often introduce it when symptoms begin to affect daily life, not just in the final days or weeks. A person with cancer, advanced heart failure, COPD, dementia, or another long-term illness may receive palliative support for months or even years. The “stages” do not begin with dying itself. They begin with planning.

However, at some point, the focus may shift toward what healthcare professionals sometimes call the dying pathway. This usually happens when doctors recognise that treatment will no longer reverse the illness and that the person may be entering the last months of life.

Care teams look for patterns such as:

- Increasing hospital admissions

- Rapid physical decline

- Reduced response to treatment

- Severe weight loss or weakness

- Escalating symptom burden

When this shift occurs, the care plan adapts. Instead of aiming to extend life, the team prioritises comfort, symptom control, and dignity.

It’s important to remember: these changes rarely happen overnight. Illness often moves in waves. Some people stabilise for long periods. Others decline gradually.

As a caregiver, you can ask:

- “Are we moving into end-of-life care?”

- “What changes should I expect next?”

- “How will we know when things are progressing?”

Clear conversations remove uncertainty. They also allow families to prepare emotionally and practically, without panic.

Stage 1: Creating a Personalised Care Plan

Every journey through the 5 stages of palliative care begins with a clear, personalised plan.

The care team, usually led by a GP (General Practitioner) or specialist, meets with the patient and family to understand three key things:

- What matters most to this person?

- What symptoms need immediate control?

- How should care adapt if the condition worsens?

This stage gives structure to uncertainty. Instead of reacting to crises, you create a roadmap.

What the Care Plan Covers

A strong plan usually includes:

- A summary of the terminal condition and expected progression

- Current medications and symptom control strategies

- Preferred place of care (home, hospice, hospital)

- Emergency contacts and escalation plans

- Clear documentation of treatment preferences

At this point, families often ask, “Who is then responsible for decisions if my loved one can’t speak for themselves?”

That’s where legal planning becomes essential.

Legal and Medical Decisions

During Stage 1, many people choose to put formal safeguards in place:

- Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) for health and welfare

- Advance Decision to Refuse Treatment (ADRT)

- A ReSPECT form, which guides emergency care decisions

These documents protect the person’s wishes. They also reduce conflict or confusion during emotional moments.

Why This Stage Is Important?

Caregivers often focus on the later phases, but this stage sets everything in motion. A clear plan prevents rushed decisions later. It ensures everyone understands priorities, whether that means aggressive symptom management, staying at home, or avoiding certain hospital treatments.

When you create the plan early, you reduce fear. You also gain confidence in the steps ahead.

READ MORE: Is MS Hereditary or Inherited? What Causes Multiple Sclerosis (2026)

Stage 2: Early Symptom Management and Practical Support

Once you create the care plan, the team moves into action. Stage 2 focuses on controlling symptoms early so the person can live as fully and comfortably as possible.

Many families ask, “How many forms of palliative care are there?” In practice, palliative care usually includes three core forms of support:

- Physical care – managing pain, breathlessness, fatigue, nausea, or insomnia

- Emotional support – addressing anxiety, fear, depression, or uncertainty

- Practical support – helping with daily tasks, mobility, and home adaptations

You may hear people refer to these as the 3 forms of palliative care, even though support often overlaps.

What Happens in This Stage?

The GP and specialist nurses adjust medications carefully. They aim to reduce pain without causing unnecessary sedation. They monitor symptoms closely and respond quickly to changes.

Common symptoms addressed in this phase include:

- Persistent pain

- Breathlessness

- Fatigue

- Loss of appetite

- Sleep disruption

If the person remains at home, district nurses or specialist palliative nurses may visit regularly. They teach caregivers how to administer medication safely and recognise warning signs early.

Practical Changes at Home

You may need to make adjustments to improve comfort and safety. These could include:

- Hospital beds or pressure-relieving mattresses

- Grab rails and ramps

- Mobility aids

- Oxygen therapy

In the UK, families may qualify for financial help such as the Disabled Facilities Grant. Speak to your local council early if home adaptations become necessary.

This Stage is Important…

Strong symptom control during Stage 2 often prevents emergency hospital admissions. It also allows the person to stay engaged with family, routines, and meaningful activities.

Good management here can significantly improve quality of life, even in the presence of a serious illness.

Stage 3: Emotional, Spiritual, and Psychological Support

Serious illness affects more than the body. It reshapes identity, relationships, and how someone sees their place in the human cycle of life. Stage 3 focuses on that deeper impact.

At this point, caregivers often notice emotional changes before physical ones. A person may withdraw, become anxious about the future, or struggle with fear of dying. Others begin reflecting on unfinished conversations, regrets, or spiritual beliefs.

Palliative care teams respond directly to those needs.

What Support Looks Like

The team may involve:

- Counsellors or psychologists

- Specialist palliative nurses

- Social workers

- Chaplains or spiritual advisors

This support helps patients process difficult questions, such as:

- “What happens next?”

- “How much time do I have?”

- “Have I lived well?”

Caregivers also need space to speak honestly. Many carry guilt, exhaustion, or fear but rarely admit it. Stage 3 gives you permission to say what you feel, without judgment.

Watching for Emotional Warning Signs

Emotional distress can also show up physically. Watch for:

- Severe anxiety

- Sudden mood swings

- Agitation at night

- Expressions of hopelessness

In some cases, patients develop terminal agitation, a state of restlessness or confusion that can appear in advanced illness. The care team can adjust medication and offer reassurance if this happens.

Why This Stage Is Necessary

Families sometimes underestimate this phase. They focus on medication and logistics. But emotional care often determines whether the final months feel chaotic or meaningful.

When you address emotional and spiritual needs early, you reduce panic later. You also strengthen relationships during the time that matters most.

ALSO SEE: Employment Rights Bill: What UK Care Workers Must Do Before 2026–2027

Stage 4: Terminal Care and the Final Weeks

At some point, the focus shifts fully toward terminal care. Doctors recognise that the illness no longer responds to treatment and that the person may be entering the final weeks or months of life.

This stage often brings difficult questions, especially in cases like stage 4 cancer palliative care life expectancy or stage 4 cancer final weeks. Life expectancy varies widely. Some people decline rapidly. Others stabilise for longer than expected. Doctors avoid exact timelines because each body responds differently.

Instead of predicting an exact number of weeks, the care team looks for patterns.

What You May Notice in the Final Weeks

- Increasing weakness and sleeping more

- Reduced appetite and fluid intake

- Less interest in conversation

- More time spent in bed

- Greater need for assistance with basic tasks

Families supporting someone dying of heart failure: what to expect often see increasing breathlessness, swelling in the legs or abdomen, and extreme fatigue. Those observing signs of impending death after stroke may notice reduced consciousness, difficulty swallowing, or minimal responsiveness.

During this phase, doctors stop focusing on cure. They concentrate on:

- Strong pain control

- Managing breathlessness

- Preventing distress

- Supporting family at the bedside

Understanding Terminal Agitation

Some people experience terminal agitation in the final days or weeks. They may appear restless, confused, or distressed. This can feel frightening to watch, but it often results from metabolic changes as the body shuts down.

The palliative team can adjust medication quickly to reduce discomfort and help the person remain calm.

The Goal of Stage 4

This stage does not aim to prolong life at all costs. It aims to protect dignity, reduce suffering, and allow meaningful time together.

If you feel unsure whether your loved one has entered this stage, ask directly:

- “Are we now in end-of-life care?”

- “What changes should I prepare for next?”

Clear answers bring clarity during uncertainty.

What Happens in the Last 24 Hours Before Death?

The final stage of the 5 stages of palliative care often raises urgent, emotional questions. Families search for phrases like:

- last 24 hours before death

- 10 signs you’re going to die soon

- 3 minutes before death

- end of life not eating or drinking how long

- how long can you survive without food or water

Let’s approach this calmly and clearly.

Common Signs in the Last 24–48 Hours

As the body prepares to shut down, you may notice:

- Long periods of sleep or unresponsiveness

- Minimal interest in food or fluids

- Shallow or irregular breathing

- Cool hands and feet

- Changes in skin colour

- Reduced urine output

- Periods of confusion or brief alertness

Breathing may become uneven. You might hear a rattling sound in the chest. This happens because muscles weaken and saliva collects. It often sounds distressing, but usually does not cause suffering.

Families sometimes ask about the exact moment, even “3 minutes before death.” In reality, death rarely follows a dramatic pattern. Breathing gradually slows. Pauses between breaths become longer. Eventually, breathing stops.

There is usually no sudden awareness or dramatic event.

What About Not Eating or Drinking?

During the final phase, people naturally lose interest in food and fluids. This does not mean you are “letting them starve.” The body no longer processes nutrition in the same way.

When families ask, “end of life not eating or drinking how long?” the answer depends on the person’s overall condition. Once someone stops drinking entirely, survival usually lasts days rather than weeks. The care team focuses on comfort, moistening the mouth, repositioning the body, and managing symptoms.

If you wonder, “how long can you survive without food or water?”, remember: at this stage, forcing nutrition rarely improves comfort and may cause distress. The goal shifts from sustaining the body to easing its natural transition.

When to Call the GP or Nurse

Call the palliative team if you notice:

- Severe restlessness or distress

- Uncontrolled pain

- Sudden breathing difficulty

- You feel unsure about what is happening

You do not have to manage this alone.

The final hours often feel quiet, heavy, and deeply emotional. But they do not have to feel chaotic. With the right support, families can remain present, calm, and connected.

MORE: Care Policies and Procedures: How to Implement Them Correctly in 2026

Stage 5: Bereavement and Support After Death

When death occurs, care does not suddenly stop. The final stage of the 5 stages of palliative care focuses on supporting the people left behind.

Many caregivers feel an immediate shift, from constant responsibility to sudden silence. Relief, sadness, guilt, numbness, even anger can appear at the same time. All of these reactions are normal.

What Happens Immediately After Death?

If your loved one dies at home, the GP or out-of-hours doctor will confirm the death. The nurse may guide you through what happens next, including contacting the funeral director.

Hospice or hospital staff usually support families directly and explain each step clearly.

Take your time. There is no need to rush decisions in the first hours.

Emotional Impact on Caregivers

Caregivers often struggle more than they expect. You may feel:

- Exhaustion after weeks or months of vigilance

- Loss of identity after intense caregiving

- Anxiety once routine disappears

Many hospices and palliative teams offer bereavement services for months after death. This may include:

- Grief counselling

- Support groups

- One-to-one conversations

- Practical guidance on paperwork and next steps

If grief begins to feel overwhelming, especially if sleep, appetite, or daily functioning collapse, speak to your GP. Support exists, and asking for help does not weaken you.

Moving Forward

Palliative care recognises that illness affects entire families, not just one person. That is why this final stage matters. Healing does not happen overnight. But support, understanding, and space to process the experience help families rebuild gradually.

You cared. You showed up. You stayed present. That matters.

When Should You Call the GP or Palliative Care Team?

During the later palliative care stages of dying, changes can happen quickly. As a caregiver, you do not need to guess whether something is “serious enough.” If you feel unsure, call.

You should contact the GP, district nurse, or specialist palliative team if you notice:

- Pain that current medication does not control

- Severe breathlessness or sudden changes in breathing

- Repeated vomiting or inability to swallow medication

- Intense restlessness or distress (including terminal agitation)

- Sudden confusion or collapse

- You feel frightened or overwhelmed by what you’re seeing

In the final phase, sometimes described in healthcare as the dying pathway, the body follows a natural shutdown process. Even so, good palliative care never ignores suffering. The team can adjust medication, provide anticipatory drugs, and guide you through what to expect next.

If death feels close, for example, breathing becomes irregular, long pauses occur between breaths, or the person becomes unresponsive, contact the nurse if you need reassurance. You are not wasting anyone’s time.

Clear communication prevents panic. It also ensures your loved one remains comfortable.

You are part of the care team. Your observations matter. If something feels different, say so.

Final Thoughts…

The 5 stages of palliative care do not represent a countdown. They represent structure during uncertainty.

Serious illness changes routines, roles, and relationships. It forces families to make decisions they never expected to face. But when you understand how care advances, from planning, to symptom control, to emotional support, to terminal care, and finally to bereavement, you regain clarity.

Palliative care does not mean giving up. It means choosing comfort, dignity, and thoughtful preparation.

When families understand what happens in the final weeks, the last 24 hours before death, or during end-of-life changes like reduced eating and drinking, fear becomes knowledge. And knowledge brings steadiness.

You do not control the timeline of illness. But you can control how prepared you feel.

Supporting Safe, Structured Palliative Care in the UK?

If you searched “5 stages of palliative care,” “does palliative care mean death,” “end of life care vs palliative care,” or “stage 4 cancer palliative care life expectancy,” you are likely supporting someone through serious illness, or managing a care service responsible for delivering safe end-of-life support.

Clear, accurate information matters. Unstructured care planning, unclear documentation, and inconsistent symptom management increase distress for families and risk for providers.

Care Sync Experts supports families, caregivers, and care providers across the UK with:

- Clear interpretation of CQC, RQIA, and CIW expectations for end-of-life care

- Governance frameworks for domiciliary care and supported living services

- Structured care planning systems aligned with NICE and NHS standards

- Policy development for palliative and terminal care documentation

- Medication governance guidance for symptom management

- Workforce competency systems for end-of-life care delivery

- Tender-writing support for services providing palliative or hospice-level care

- Inspection readiness audits for services supporting terminal conditions

Whether you are caring for a loved one, strengthening your care workforce, or managing a regulated service, we help you move from uncertainty to structured, evidence-based systems.

Get in touch with Care Sync Experts today and ensure your palliative care delivery is compliant, confident, and built to withstand inspection and commissioning scrutiny.

FAQ

What Are the 4 Pillars of Palliative Care?

Healthcare professionals often describe palliative care using four foundational pillars:

Symptom control – managing pain, breathlessness, nausea, fatigue, and other physical symptoms

Psychological support – addressing anxiety, depression, fear, and emotional distress

Social support – helping with family dynamics, practical needs, and community resources

Spiritual care – supporting meaning, beliefs, values, and existential concerns

These pillars work together. Good palliative care does not treat symptoms in isolation; it supports the whole person and their family.

What Are the Three Main Goals of Palliative Care?

Although frameworks vary, most professionals agree that palliative care has three primary goals:

Relieve suffering – control pain and distressing symptom

Improve quality of life – preserve comfort, dignity, and independence where possible

Support informed decision-making – help patients and families understand options and plan ahead

These goals apply whether someone lives with a chronic illness for years or enters the final phase of life.

What Are the Four Essential Drugs in Palliative Care?

In end-of-life situations, clinicians often keep four key medications available to manage common symptoms quickly. While specific drugs vary by patient and setting, they usually address:

Pain (typically opioids such as morphine)

Breathlessness (often managed with low-dose opioids or other respiratory support)

Anxiety or agitation (such as midazolam for severe distress)

Nausea or secretions (medications like antiemetics or anticholinergics)

Doctors prescribe these carefully and adjust them based on individual needs. Families should never administer medication without clear clinical instruction.

What Is the 80/20 Rule in Hospice?

The “80/20 rule” in hospice refers to funding and eligibility guidelines in some healthcare systems, not to medical treatment decisions.

In simple terms, hospice care is typically offered when clinicians believe there is a high likelihood (often described as around 80%) that a person may be in the final months of life if the illness follows its expected course.

It does not mean doctors can predict death with 80% certainty. Prognosis remains complex and individual.

Hospice teams regularly reassess patients. If someone stabilises or improves, care plans adjust accordingly.

Would you like to receive update from CareSync Experts?