First Person vs Third Person Care Plan:

CQC and the Mental Capacity Act Expectation in 2026

Text to speech

Duration: 00:00

Font size

Published: 5 Feb, 2026

Share this on:

Care teams have argued about first person versus third person care plans for years. One side believes “I prefer…” language protects dignity and voice. The other worries it confuses staff and risks putting words into someone’s mouth. In 2026, that argument matters far less than many providers think.

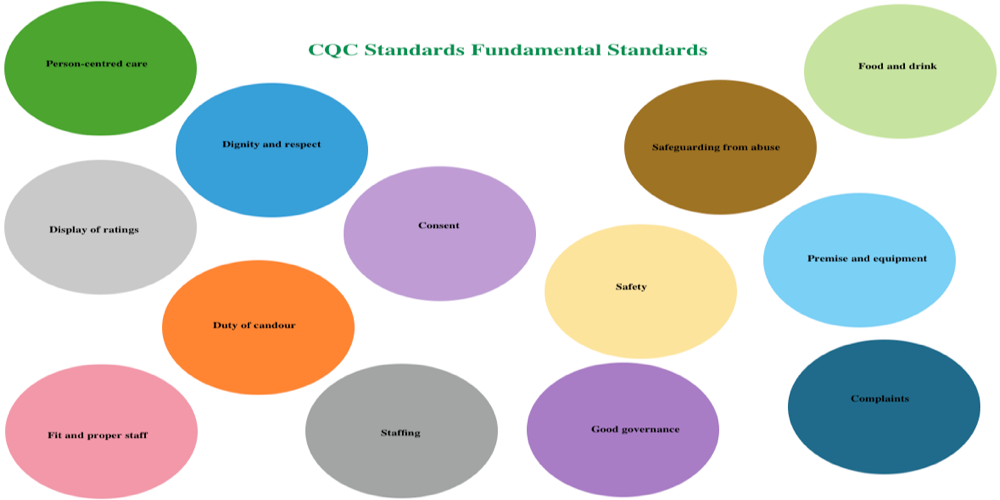

CQC no longer focuses on the grammar of a care plan. Inspectors now test something deeper: can you prove the person sits at the centre of their care, even when they need support to express wishes or make decisions? They look for evidence of involvement, honest recording, and plans staff can actually follow.

This guide cuts through opinion and shows what works now. You’ll learn what regulators expect, where teams go wrong, and how to build care plans that stay person centred, accurate, and inspection-proof.

The 2026 Reality: Inspectors Test Evidence, Not Grammar

In 2026, CQC inspections no longer reward how a care plan sounds. Inspectors focus on what the plan proves. They ask whether the person genuinely shaped their care, whether staff can act on the plan safely, and whether records show ongoing review and change.

Under the Care Quality Commission Single Assessment Framework, inspectors use quality statements and “I statements” to understand people’s experiences. These statements describe what good care feels like from the person’s perspective. They are not templates for how you must write your documentation. CQC uses them as an evidence lens, not a grammar rule.

When inspectors open a care plan, they test three things:

- Involvement: Who helped create this plan, and how do you know?

- Accuracy: Where did each key preference come from, and is it still current?

- Usability: Can staff read this and deliver consistent, safe care?

If a plan answers those questions clearly, it meets expectations whether it uses first person, third person, or a mix of both. If it cannot, the wording won’t save it.

This shift explains why many providers now adopt a person centred approach that blends voice with clarity. CQC wants to see care planning that reflects real lives, supports patient centred care, and holds up under scrutiny. The strongest plans put the person at the centre, show honest evidence of how decisions were made, and guide staff without confusion.

Regulation 9 in Plain English: What Your Care Plan Must Prove

Regulation 9 sits at the heart of every inspection conversation about care planning. It does not tell you how to write. It tells you what your care plan must demonstrate in practice.

In simple terms, Regulation 9 expects your care planning to prove four things:

- The care fits the person, not the service

The plan must reflect the individual’s needs, preferences, and outcomes. Generic wording signals weak personalisation, even if it sounds polite or “person centred”.

- The person was involved, or lawfully represented

The person should take part in planning and review wherever possible. If they cannot, the plan must show how family members, advocates, or others acting lawfully on their behalf contributed.

- Preferences influence real decisions

It is not enough to list likes and dislikes. Inspectors look for a link between what matters to the person and how staff actually support them day to day.

- The plan evolves as needs change

A care plan must stay live. Reviews, updates, and changes should appear clearly in the record, not buried in daily notes.

This is where many services fall down. A plan may read warmly, but if it does not show involvement, decision making, and review, it fails the regulation. Poor care planning under Regulation 9 often triggers wider concerns around dignity, consent, and safety because staff rely on the plan to guide their actions.

A strong person centred care record makes these links obvious. It shows who contributed, what changed, and how staff adjusted their support. When your care plans do that consistently, grammar becomes irrelevant, and compliance becomes visible.

The Mental Capacity Act: The Rule That Changes How You Write Preferences

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) shapes how every care plan should be written when capacity comes into question. In 2026, inspectors expect teams to understand this law in practice, not just quote it in policies.

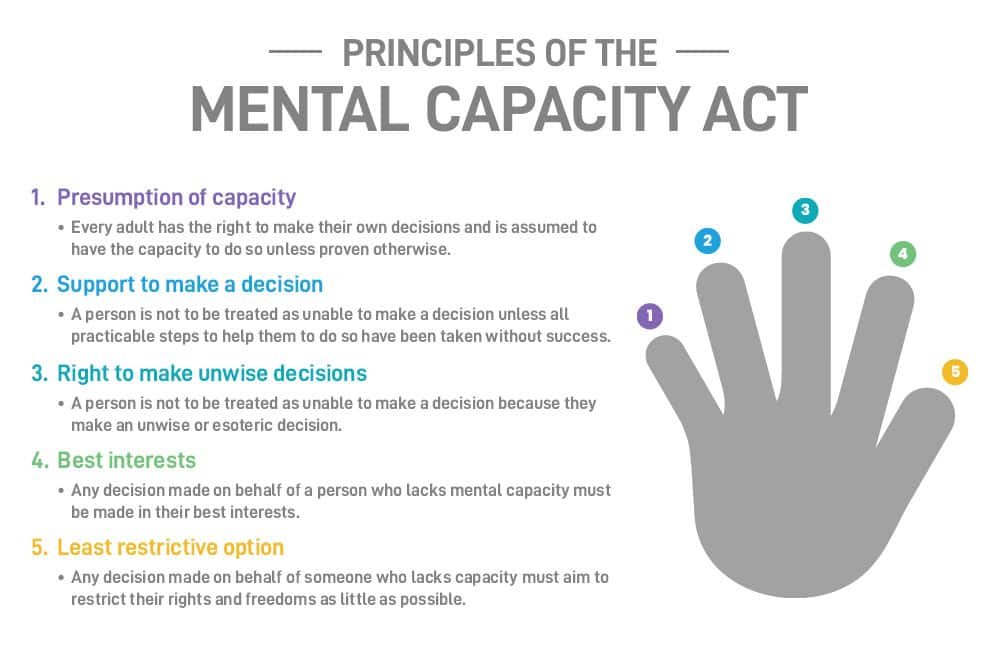

The MCA sets out five principles that directly affect care planning:

- Assume capacity unless you have evidence otherwise

- Support decision-making before deciding someone cannot decide

- Respect unwise decisions if the person has capacity

- Act in best interests when capacity is lacking

- Choose the least restrictive option possible

These principles make one thing clear: capacity is decision-specific, not global. A person may decide what they want to wear but not understand complex medication choices. Your care plan must reflect that nuance.

This is where writing style becomes risky.

Writing “I prefer…” works well when the person has clearly expressed that preference. It becomes dangerous when the preference actually came from staff inference, family opinion, or a best interests discussion. Inspectors may ask a simple but critical question: “How do you know this is what the person wants?”

A care plan that cannot answer that question exposes the service to challenge. It may look person centred on the surface, but it fails legal accuracy. In contrast, a plan that clearly separates expressed wishes, observed responses, and best interests decisions stands up to scrutiny.

In 2026, strong person centred care does not mean pretending someone spoke when they could not. It means recording wishes honestly, supporting choice wherever possible, and documenting decisions properly when others must act on the person’s behalf.

READ MORE: Latest CQC Reports, Regulated Activities (2026)

First Person Care Plans: When They Work and When They Backfire

First person care plans can work beautifully when teams use them honestly. They can also create real risk when teams treat them as a template instead of a reflection of real voice.

When First Person Care Plans Work Well

First person language works best when the person can express their wishes and actively shape their care. Writing “I feel rushed in the mornings” or “I like my room kept tidy” reminds staff that they support a person, not a task list.

Used properly, first person writing:

- Strengthens dignity and identity

- Makes involvement visible

- Supports co-production during reviews

- Helps staff connect emotionally with the person

When teams write a care plan alongside the individual and record their actual words, inspectors see clear evidence of involvement. This approach aligns naturally with a person centred approach because it shows choice, control, and ownership.

Where First Person Care Plans Go Wrong

Problems start when first person language stops reflecting reality.

Some plans rely on stock phrases like “I like to be treated with dignity” or “I enjoy socialising.” These statements tell inspectors nothing about the person. They signal that staff copied a template instead of listening.

First person language also fails when teams guess. Writing “I prefer female carers” without evidence of the person saying this can mislead staff and misrepresent the individual. For people with advanced dementia or long-term non-verbal communication, this can feel like speaking on their behalf without justification.

First person plans can also confuse staff. Instructions written as “I need help with transfers” do not always make it clear who must act, how, or when. In busy environments, that lack of clarity can undermine safe care.

A person-centred care plan example only works when the voice is real. When first person language hides assumptions or replaces evidence, it weakens both care quality and inspection confidence.

Third Person Care Plans: When They Protect Safety and Clarity

Third person care plans play a critical role in safe, consistent care. In 2026, many providers rely on them for the parts of a care plan that demand precision, accountability, and clear staff action.

When Third Person Care Plans Work Well

Third person writing excels where clarity matters most. Statements like “Staff must ensure the walking frame is within reach at all times” remove ambiguity. They tell carers exactly what to do and reduce the risk of missed steps or unsafe assumptions.

Third person language works best for:

- Step-by-step support instructions

- Risk management and control measures

- Clinical observations and assessments

- Professional recommendations and escalation pathways

This approach fits naturally with clinical documentation and assessment tools. Writing “The person is at high risk of falls” accurately reflects a professional judgement. It avoids the awkwardness and inaccuracy of turning clinical risk into a first person statement.

For people who cannot reliably express preferences, third person writing also protects honesty. It allows staff to record what they observe and what professionals recommend without pretending the person said something they did not.

Where Third Person Care Plans Go Wrong

Problems arise when third person plans lose the person entirely.

Plans written only as task lists can feel cold and impersonal. Phrases like “Service user requires assistance with personal care” reduce a person to a set of needs. Inspectors often see this as a sign that the plan serves the service, not the individual.

Third person plans also fail when they disconnect risks from actions. Identifying a risk without clear instructions leaves staff unsupported and increases the chance of errors.

Used well, third person language strengthens safety and consistency. Used poorly, it strips away identity and undermines a person centred approach. This tension is exactly why most high-performing services no longer choose one style over the other.

SEE ALSO: What does CQC stand for? Complete 2026 Guide

Best Practice in 2026: The Hybrid Care Plan Model Services Can Standardise

In 2026, the strongest services no longer argue about first person versus third person. They use a hybrid care plan model that balances voice, accuracy, and staff clarity. This approach meets regulatory expectations and works in real care settings.

The hybrid model accepts one simple truth: different parts of a care plan serve different purposes. Trying to force one writing style across everything usually creates risk.

Section A: “About Me and What Matters”

This section captures identity, preferences, and personal context. Write it in first person wherever the person’s voice is authentic and evidenced.

Use this space to record:

- Life history and background

- Daily routines and preferences

- Likes, dislikes, and triggers

- Important relationships

- Cultural, spiritual, and religious needs

- Communication preferences

- Hobbies and interests

This is where person centered activity care plans naturally sit. The focus stays on who the person is, not just what support they receive.

Section B: “How Staff Support Me”

This section translates preferences into action. Write it in clear third person instructions so staff know exactly what to do.

Use language like:

- “Staff must…”

- “Staff should…”

- “Ensure that…”

Cover areas such as:

- Personal care support

- Mobility and transfers

- Nutrition and hydration

- Communication approaches

- Daily routines

This is where a care plan becomes usable in practice.

Section C: Risk and Clinical Information

This section must prioritise accuracy and safety. Write in third person and reference professional guidance where relevant.

Include:

- Risk assessments and scores

- Control measures and monitoring

- Escalation procedures

- Clinical observations and recommendations

This structure supports safe care and reduces confusion during incidents or inspections.

Section D: Evidence, Capacity, and Review

This section protects your service during inspection. It shows how decisions were made and who was involved.

Record:

- Who contributed to the plan

- Capacity assessment outcomes

- Best interests decisions

- Consent documentation

- Review dates and changes

Together, these sections create a person centred approach that is consistent, defensible, and easy to audit. Services that standardise this structure across every individual support package build confidence for staff and inspectors.

LEARN MORE: CQC Registration for Domiciliary Care Providers: Complete 2026 Guide

The Skill That Makes Care Plans Inspection-Proof: Honest Attribution

Honest attribution is the single most important skill in modern care planning. It turns a well-written care plan into one that stands up to inspection, safeguarding reviews, and legal scrutiny.

CQC does not expect providers to guess what someone wants. Inspectors expect services to show where information came from and how decisions were reached. When teams fail to do this, plans may look person centred but collapse under questioning.

Why Attribution Matters

Inspectors often ask simple follow-ups:

- “How do you know this preference?”

- “When did the person say this?”

- “Who was involved in this decision?”

If the care plan cannot answer those questions clearly, it signals weak governance, even if the wording sounds compassionate.

Attribution protects the person, the staff, and the service. It keeps records honest and avoids presenting assumptions as facts.

A Simple Source System You Can Use Everywhere

For every key preference, routine, or restriction, record the source clearly:

- Source: person stated

The person directly expressed this preference.

- Source: family reported

A family member or close contact shared this information.

- Source: staff observation

Staff identified this through consistent observation over time.

- Source: best interests decision

The preference or action was agreed through a formal best interests process.

- Source: professional guidance

A healthcare professional recommended this approach.

This system works across all parts of the care plan. It supports person centred care without pretending the person spoke when they could not.

What Honest Attribution Looks Like in Practice

Instead of writing:

“I prefer female carers.”

Write:

“What matters to me: I appear calmer when supported by female carers where possible.

Source: staff observation over six weeks, confirmed by family. Best interests decision recorded on [date].”

This approach keeps the person at the centre while remaining accurate. It also gives staff confidence and makes inspection conversations straightforward.

In 2026, attribution matters more than grammar. Services that build this habit into every care plan consistently deliver safer, more defensible, and genuinely person-centred care.

Practical Care Plan Examples You Can Adapt

This section shows how the hybrid model works in real life. Each example keeps the person at the centre while giving staff clear, safe instructions. These formats also hold up well during inspection because they show involvement, attribution, and action.

Example 1: Person-centred Care Plan Example (Personal Care)

Section A: What Matters to Me

I prefer to wash at the sink rather than showering. Showers make me feel cold and anxious. I like to take my time in the mornings and do not like being rushed.

Source: Person stated on 12 March 2026. Reviewed and confirmed on 10 April 2026.

Section B: How Staff Support Me

Staff must offer a sink wash each morning as the first option.

If [Name] declines, offer a shower as an alternative but do not persist if distress increases.

Ensure privacy at all times by closing doors and curtains.

Explain each step before providing support.

Allow [Name] to complete tasks independently where safe.

Section C: Risk and Clinical Information

[Name] has reduced balance when standing for long periods.

Non-slip mat must be used.

Staff to remain within arm’s reach during washing.

Example 2: Medication Care Plan Examples (Including Nursing Context)

This example shows how to combine clarity with safety in a nursing care plan for medication.

Section A: What Matters to Me

I want to understand what my medication is for. I feel anxious if tablets are given without explanation.

Source: Person stated during medication review on 5 February 2026.

Section B: How Staff Support Me

Staff must explain the purpose of each medication before administration.

Medication must be administered as per MAR chart.

PRN medication:

- Only administer if pain score is above 4/10

- Record reason, dose, and outcome clearly

Staff must check for side effects including dizziness, nausea, or confusion, and report concerns to the senior carer immediately.

Section C: Risk and Clinical Information

[Name] takes medication for hypertension and diabetes.

Risk of hypoglycaemia identified.

Monitoring:

- Blood glucose monitoring as per care protocol

- Escalate readings outside agreed range to GP the same day

This structure supports safe practice while keeping the person informed and involved.

Example 3: Person-Centered Activity Care Plans

Section A: What Matters to Me

I enjoy music from the 1970s and like listening to it in the afternoon. It helps me relax and improves my mood.

Source: Family reported. Confirmed through staff observation over four weeks.

Section B: How Staff Support Me

Staff should offer music sessions in the afternoon using [Name]’s playlist.

Encourage gentle movement or singing if [Name] appears engaged.

If [Name] shows signs of fatigue or distress, stop the activity and offer a quiet alternative.

Outcome Focus

Activity participation supports emotional wellbeing and reduces agitation.

Record responses in daily notes to guide future support.

Why These Examples Work

Each care plan example:

- Separates voice from instruction

- Shows where information came from

- Links preferences to staff actions

- Connects risks to clear controls

This structure supports consistent care, strengthens inspection confidence, and keeps the person genuinely at the centre rather than just sounding centred on paper.

READ THIS: Harrow Council Home Care Tender 2026

Digital Care Planning in 2026: Use Software to Support Practice, Not Replace It

Digital systems now sit at the centre of modern care planning, but software alone does not make a care plan person centred. In 2026, inspectors look at how teams use systems, not which platform they buy.

Good person centred software supports clarity, accountability, and review. It helps teams record involvement, track changes, and show evidence quickly. Poor use of software, however, often hides weak practice behind neat screens.

What Inspectors Expect to See in Digital Care Plans

Regardless of platform, strong systems allow teams to:

- Record who contributed to each section of the plan

- Show clear version history and review dates

- Separate preferences from instructions and clinical content

- Evidence capacity assessments and best interests decisions

- Track changes over time, not overwrite history

When inspectors ask to see how a care plan has evolved, your system should make that visible within minutes.

Common Searches and What They Really Mean

Many providers search for tools using terms like log my care, pcs login, person centred software login, or internal systems such as a psc intranet. Others ask about software to software integration so care records link with rostering, medication, or reporting systems.

These searches reflect a practical need: teams want systems that save time and reduce duplication. What matters most is not the brand, but whether the software supports good practice.

A digital system should never force teams into generic templates. It should allow real personalisation, clear attribution, and structured review. If staff cannot explain how the system supports person centred care in practice, inspectors will question its value.

Used well, digital tools strengthen consistency and governance. Used poorly, they mask problems. In 2026, the strongest services use software to support thinking, not replace it.

How Does Person-Centred Care Improve Health Outcomes?

Person-centred care improves health outcomes because it changes how people engage with their support. When a care plan reflects what genuinely matters to someone, care stops feeling imposed and starts feeling collaborative.

In practice, services that use a strong person centred approach see clearer, measurable benefits:

- Better adherence to care and medication

People are more likely to accept support and follow routines when plans reflect their preferences. Clear explanations and involvement reduce resistance and missed doses.

- Reduced distress and behavioural escalation

When staff understand triggers, routines, and communication preferences, they intervene earlier and more appropriately. This often leads to fewer incidents and less reliance on restrictive responses.

- Improved safety and continuity

Care plans that link risks to clear actions help staff respond consistently. This reduces avoidable falls, medication errors, and unplanned escalations.

- Stronger trust with families and professionals

Families gain confidence when they see honest, reviewed documentation that reflects real involvement. Professionals can work more effectively when care plans align with wider clinical goals, including elements of an NHS health plan where relevant.

Most importantly, person-centred care supports dignity and autonomy. People feel heard, respected, and involved, even when they need support to make decisions. That sense of control often underpins better physical, emotional, and psychological outcomes.

When teams ask how person-centred care improves health outcomes, the answer is simple: it works because it treats people as active participants in their own lives, not passive recipients of services.

MORE: Price of Long Term Care in the UK: Care Home Costs (2026 Guide)

The 1-Minute Compliance Checklist (Use This Before Any Inspection)

Before an inspection, a manager should be able to open any care plan and answer these questions confidently. If the answer is “no” to any of them, the plan needs work.

Person at the centre

- Does the plan clearly show what matters to the person, not just what tasks staff complete?

- Can staff explain how the plan reflects the person’s routines, preferences, and priorities?

Evidence of involvement

- Does the plan record who contributed to it?

- Is it clear when the person was involved directly and when others supported decision making?

Honest attribution

- Can the team explain where each key preference came from?

- Are best interests decisions clearly recorded when capacity is lacking?

Safe and usable

- Do identified risks link to clear actions, monitoring, and escalation?

- Can a new staff member follow the plan without guessing?

Reviewed and current

- Has the plan been reviewed recently?

- Do reviews show real changes when needs, risks, or preferences changed?

Care plans that pass this checklist usually perform well under inspection. They demonstrate person centred thinking, legal awareness, and operational clarity without relying on stylistic tricks.

If your service struggles to apply this consistently, the issue is rarely grammar. It is usually systems, training, or governance. Fix those, and your care planning will speak for itself.

Conclusion

By 2026, the debate over first person versus third person care plans has largely missed the point. CQC does not inspect grammar. Inspectors inspect evidence.

The strongest care plans do not ask, “Should we write ‘I’ or ‘they’?” They ask, “Can we prove this plan reflects the person’s life, their wishes, and the decisions made on their behalf?” When a care plan shows clear involvement, honest attribution, and instructions staff can follow, it meets expectations regardless of writing style.

First person language has real power when it captures authentic voice. Third person language protects accuracy, safety, and clarity. A hybrid approach brings those strengths together and removes the risks. It allows teams to honour identity without guessing, and to deliver safe care without losing humanity.

Ultimately, a care plan is not a document for inspection day. It is a working tool that shapes daily support, staff behaviour, and outcomes. When teams focus less on how a plan sounds and more on what it proves, care becomes more consistent, more defensible, and more human.

Get the fundamentals right, and the question of voice stops being a problem. It becomes a tool.

Ready to make your care plans inspection-proof?

Strong care plans do more than sound person centred. They prove involvement, support safe practice, and stand up to scrutiny under the CQC Single Assessment Framework and the Mental Capacity Act. In 2026, inspectors look for evidence, not just language.

Care Sync Experts supports care providers across England, Wales, and Northern Ireland with:

- Care plan structure and hybrid model implementation

- Person-centred care plan reviews aligned to Regulation 9

- Mental Capacity Act and best interests documentation support

- Medication and risk care plan development

- Staff training on honest attribution and inspection-ready recording

- Ongoing compliance, audits, and inspection preparation

Whether you need a full service-wide care planning overhaul or targeted support to strengthen existing documentation, we help you build care plans that are clear, defensible, and genuinely person centred.

Get in touch with Care Sync Experts today to bring clarity, confidence, and consistency to your care planning.

FAQ

Which framework considers the individual needs of patients to provide better quality care?

The most widely recognised framework is the Person-Centred Care framework.

In the UK health and social care context, this approach focuses on understanding the individual’s values, preferences, life history, and goals, and then shaping care around those factors rather than around routines or services.

In practice, this means:

– Care starts with who the person is, not what tasks need doing

– Decisions reflect what matters to the individual

– Care adapts as needs, preferences, or circumstances change

This framework underpins how regulators like CQC assess whether care planning is genuinely personalised rather than procedural.

What is person-centred care (McCormack and McCance)?

Brendan McCormack and Tanya McCance developed one of the most influential academic models of person-centred care, widely used in nursing and healthcare education.

Their framework explains person-centred care as a combination of:

Practitioner attributes (values, competence, self-awareness)

Care environment (culture, systems, leadership)

Care processes (engagement, shared decision-making, empathy)

Person-centred outcomes (satisfaction, well-being, involvement)

The key takeaway is this: person-centred care is not just about how you write care plans. It depends on staff behaviour, organisational culture, and how care is delivered day to day.

This is why strong documentation alone never guarantees good care.

What are the 5 Ps of patient care?

The 5 Ps of patient care are a simple model often used in healthcare to ensure holistic support.

While wording can vary slightly, they are commonly described as:

Purpose – Why the care or intervention is needed

Pain – Physical or emotional discomfort that must be addressed

Position – Comfort, safety, and physical alignment

Personal needs – Toileting, hygiene, nutrition, dignity

Prevention – Reducing risks such as falls, pressure damage, or infection

This framework helps teams look beyond tasks and check whether care is meeting both clinical and human needs. It is often used alongside care planning rather than replacing it.

Which framework is commonly used for quality improvement in healthcare?

One of the most commonly used frameworks is the Plan–Do–Study–Act (PDSA) cycle.

It supports continuous improvement by encouraging teams to:

Plan a change

Do it on a small scale

Study the results

Act on what was learned

In care settings, PDSA cycles often support improvements in areas like:

– Care planning quality

– Medication safety

– Communication practices

– Review and audit processes

While PDSA is not a care planning framework, inspectors often expect services to show how they use structured improvement methods to respond to issues identified through audits, incidents, or feedback.

Would you like to receive update from CareSync Experts?