Starting a Care Home in the UK:

Best 2026 Guide

Text to speech

Duration: 00:00

Font size

Published: 23 Jan, 2026

Share this on:

Starting a care home in the UK means registering with the Care Quality Commission (CQC) before you provide any residential care for adults in England.

To open a care home, you must register the provider (and usually a registered manager), define the regulated activities you’ll deliver, prove you can meet quality and safety standards, and prepare for inspection.

Most delays happen because owners secure property or hire staff before they design the service around CQC expectations, so start with compliance, then build everything else around it.

How to start a care home: pick your care model first

Before you apply to CQC or spend money on property, decide what kind of care home you’re actually opening. This single decision shapes your registration route, staffing, costs, and long-term risk.

Residential care homes (most common starting point)

Residential care homes support adults who need help with daily living, washing, dressing, eating, mobility, and medication prompts, but not 24-hour nursing care.

If this is your first time starting a care home, this model usually makes sense because:

- Registration is more straightforward

- Staffing requirements are lower than nursing homes

- Startup and operating costs are easier to control

- Demand is strong in most local authority areas

Many first-time owners choose residential care, build a strong compliance record, then expand later.

Nursing homes (higher risk, higher complexity)

Nursing homes provide everything a residential home does plus continuous nursing care. You’ll need registered nurses on duty, more complex clinical governance, and higher insurance cover.

Choose this route only if:

- You already have nursing leadership in place, or

- You’re converting or acquiring an existing nursing home, or

- You’ve secured funding that supports higher staffing and clinical costs

If you underestimate the clinical side, inspectors will spot it quickly.

Specialist care homes (dementia, learning disability, mental health)

Specialist homes focus on a specific need, such as dementia or learning disabilities. These services attract strong demand, but inspectors expect evidence of specialist training, adapted environments, and tailored care models from day one.

Specialism works best when:

- You have direct experience with the client group

- Your location already has referral pathways

- Your staffing plan reflects the higher support needs

Respite care homes (short-stay focus)

Respite care provides short-term placements for people whose usual carers need a break or who are transitioning from hospital. While stays are shorter, standards are not lighter. You still need full compliance, safe staffing, and strong admission controls.

A simple decision rule

If you’re unsure how to start a care home, use this rule:

Start with the least complex care model you can run safely, then scale once you’ve passed inspections and stabilised occupancy.

CQC does not reward ambition. It rewards clarity, safety, and control.

How to open a care home in England: what CQC expects

If you want to open a care home in England, you must register with the Care Quality Commission (CQC) before you provide any regulated care. You cannot trade first and “sort registration later.” Doing so is a criminal offence and will end your application before it starts.

You register the provider, and usually the manager too

CQC does not register buildings. It registers people and organisations.

You must apply as the service provider, which can be:

- A limited company

- A partnership

- An individual (sole trader)

If the provider is an organisation or partnership, CQC will also expect you to appoint and register a registered manager who takes day-to-day responsibility for the service.

If you apply as an individual and intend to manage the home full time yourself, you may not need a separate manager, but CQC will still assess you against the same standards.

The key question inspectors ask is simple: Who is legally accountable for safe, well-led care every day?

What you submit with your CQC application (plain English)

CQC applications fail when owners treat them like paperwork. In reality, this is where you prove you understand the business you’re starting.

You must clearly set out:

- Each location where you will deliver residential care

- The regulated activities you intend to carry out

- Who your service is for and who it is not for

- How you will meet quality and safety standards

- A formal declaration of compliance

CQC will also assess:

- Your governance structure

- Your ability to recruit, train, and supervise staff

- Your financial viability

- Your understanding of safeguarding, medicines, and risk management

There is no application fee, but once CQC grants registration, you must pay an annual fee to remain registered.

A critical warning (where most people go wrong)

Many first-time owners secure property, buy equipment, or hire staff before they fully understand what CQC expects. That approach increases cost and risk.

A safer rule when starting a care home in the UK is this: Design the service on paper first, prove it meets CQC standards, then commit money.

CQC approves services that show control, clarity, and realistic planning, not enthusiasm alone.

What inspectors actually look for (so you build the right service)

When CQC assesses your application and later inspects your care home, inspectors don’t look for perfection. They look for control. They want clear evidence that you understand your risks and manage them every day.

Staffing: enough people, with the right skills

There is no legal staff-to-resident ratio for care homes. Instead, inspectors judge whether you provide sufficient, competent staff to meet residents’ needs at all times.

In practice, this means you must be able to show:

- How many staff you need on each shift

- Why that number works for your residents’ needs

- How you cover sickness, holidays, and emergencies

- How staff receive training, supervision, and support

If you can’t explain your staffing logic clearly, inspectors will assume it isn’t safe.

Safeguarding and risk management

Inspectors expect safeguarding to run through everything you do, not sit in a policy folder.

They will look for:

- Clear safeguarding procedures that staff actually understand

- Risk assessments tailored to individual residents

- Evidence that staff know how to raise concerns and act quickly

Good providers don’t just react to incidents. They anticipate risk and reduce it early.

Medicines and records

Medication errors trigger serious enforcement action. Inspectors will check whether you:

- Store medicines safely

- Administer them correctly

- Keep accurate, up-to-date records

- Act quickly when something goes wrong

The same standard applies to care records. Inspectors expect notes that are clear, current, and reflect real care, not copy-and-paste templates.

Leadership and governance

CQC places heavy weight on whether a service is well-led. Inspectors want to see:

- Clear responsibility at management level

- Regular audits and checks

- Evidence that you learn from mistakes

- Systems that improve care over time

This applies even to small homes. Size does not reduce accountability.

The inspection mindset you need

If you’re starting up a care home, adopt this mindset early: If you can’t evidence it clearly, you can’t defend it.

Strong services don’t rely on goodwill or hard work alone. They rely on systems that work even on bad days.

Starting a care home UK, a practical setup checklist

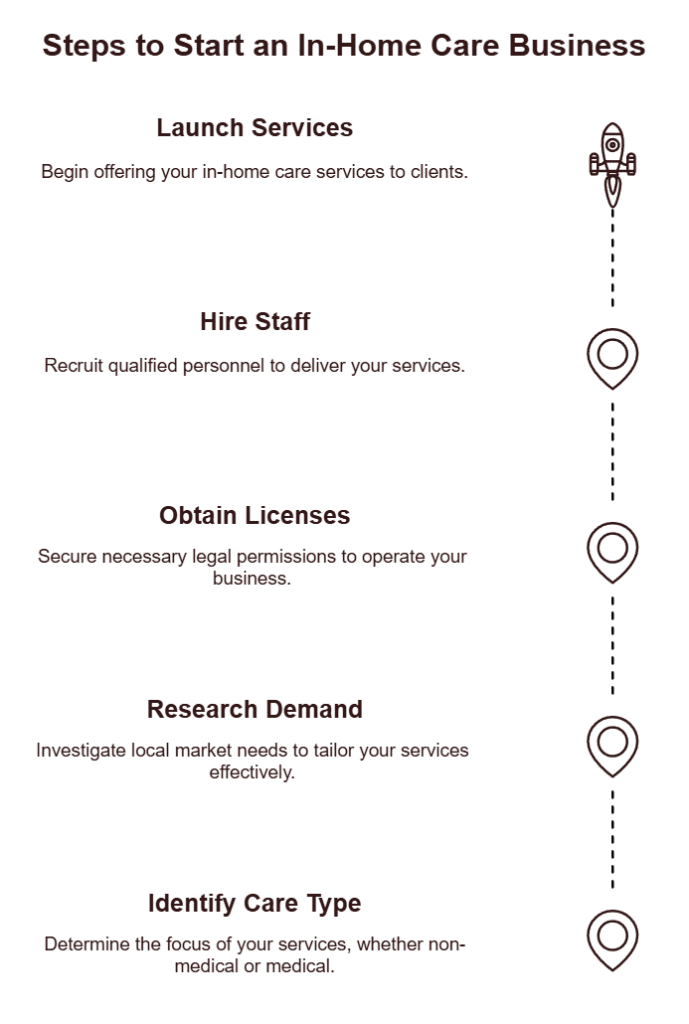

Once you understand the care model and CQC expectations, you can move into setup. The order matters. Follow these steps to avoid wasted money, failed applications, and long delays.

1) Confirm demand and referral routes

Start with evidence, not assumptions.

- Check local authority commissioning priorities

- Identify who will refer residents (councils, hospitals, families)

- Define the exact needs you will accept, and those you won’t

Clear admission criteria protect residents and your registration.

2) Secure a suitable property (with safety in mind)

Choose a building that can realistically meet care standards.

- Adequate space for mobility aids and equipment

- Safe access and evacuation routes

- Fire safety suitability from day one

Avoid heavy renovations until your service model and compliance plan are clear.

3) Build your compliance pack before hiring

Create the core documents that prove control:

- Safeguarding procedures

- Medicines management

- Staffing and supervision plans

- Risk assessments

- Governance and audit processes

Inspectors expect these systems to exist before residents arrive.

4) Appoint or identify your registered manager

CQC places major responsibility on leadership.

- Confirm who holds day-to-day accountability

- Align their experience with your care model

- Prepare their registration alongside the provider application if required

Weak leadership delays or blocks registration.

5) Plan staffing and training realistically

Design rotas around resident needs, not minimum numbers.

- Cover nights, weekends, sickness, and leave

- Schedule induction and mandatory training

- Build supervision and appraisal into normal operations

Staffing failures cause most early enforcement action.

6) Apply to CQC with a complete, coherent application

Submit only when everything aligns:

- Service description

- Regulated activities

- Locations

- Governance systems

- Financial viability

Rushed or inconsistent applications trigger long follow-ups.

7) Prepare for inspection before it happens

Assume inspectors will arrive.

- Run internal checks

- Test procedures with staff

- Fix gaps early

The strongest providers treat inspection readiness as normal operations, not a one-off event.

Starting a care home, costs, funding, and cashflow reality

Starting a care home is capital-intensive, and most first-time owners underestimate how long it takes before income stabilises. If you plan costs realistically from the start, you protect the service and your registration.

The main cost areas to plan for

While figures vary by location and size, costs usually fall into these buckets:

- Property

Purchasing or leasing a suitable building is often the largest upfront cost. Prices vary widely by region, and not every building can meet care standards without expensive adaptations.

- Staffing (your biggest ongoing expense)

Wages typically account for the largest share of monthly outgoings. This includes care staff, management, training time, sickness cover, National Insurance, and pension contributions.

- Compliance and governance

Training, audits, record-keeping systems, insurance, and ongoing quality monitoring all carry costs. These aren’t optional extras, they’re core operational expenses.

- Equipment and environment

Beds, hoists, mobility aids, specialist seating, bathroom adaptations, and safety equipment add up quickly. Buying the right equipment early reduces injury risk and staffing strain.

- Operating costs

Utilities, food, cleaning supplies, maintenance, professional fees, and marketing all need to sit within a realistic monthly budget.

Funding options to consider

Most people starting up a care home combine several funding sources:

- Commercial mortgages for the property

- Personal or investor capital

- Business loans or asset finance for equipment

- In some cases, targeted grants linked to specialist care or innovation

Lenders and investors will expect a clear business plan, realistic occupancy assumptions, and evidence that you understand regulatory risk.

The cashflow rule that protects new services

Even well-planned care homes take time to reach stable occupancy. A safe rule is this: Plan enough working capital to run the home for several months with low occupancy.

This buffer gives you room to:

- Pass inspections without panic

- Recruit and train staff properly

- Build referrals without cutting corners

Care homes don’t fail because demand disappears. They fail when cashflow collapses before systems mature.

Business plan for a care home, what actually matters

A care home business plan is not a formality. Regulators, lenders, and partners use it to judge whether you understand the risks of starting a care home and whether your service can survive pressure.

Keep it practical. Avoid generic business language.

Executive summary (short, factual, focused)

State clearly:

- What type of care home you’re opening

- Where it will operate

- Who it will serve

- How it will stay safe, compliant, and financially viable

This section should make sense on its own.

Service model and staffing plan

Explain:

- Your care model (residential, nursing, specialist, or respite)

- Admission criteria and exclusions

- Staffing structure by shift

- How you recruit, train, and retain staff

Decision-makers want to see that staffing levels match resident needs, not optimistic assumptions.

Compliance and governance plan

Show how you will meet regulatory expectations daily:

- Safeguarding systems

- Medicines management

- Risk assessments

- Quality audits

- Incident reporting and learning

This is where many plans fail. Be specific.

Pricing and occupancy assumptions

Explain:

- How you set fees

- Expected occupancy rates

- How long it takes to reach break-even

- How council-funded placements affect cashflow

Avoid best-case scenarios. Conservative forecasts build trust.

Financial projections (minimum three years)

Include:

- Startup costs

- Monthly operating costs

- Cashflow forecasts

- Contingency planning

Inspectors and lenders look for realism, not ambition.

Risk management

Identify the risks most likely to damage the service:

- Staffing shortages

- Inspection failure

- Low occupancy

- Rising costs

Then explain how you reduce and manage them.

A final business-plan rule

If your business plan can’t explain how the care home stays safe on a bad week, it isn’t finished.

How to set up a care agency instead (domiciliary care)

Many people who search for how to start a care home later realise that a residential setting isn’t the right first step. If you want lower startup costs and more flexibility, setting up a care agency (domiciliary care) may be a better option.

This model lets you deliver care in people’s homes rather than running a fixed premises.

How do I start a care agency?

If you’re asking how do I start a care agency, the process still begins with regulation, but the structure is different.

In England, you must register with the Care Quality Commission to provide personal care in people’s homes. As with care homes, you register the provider, and usually a registered manager, before delivering any care.

The key difference is scale:

- No residential property to buy

- Lower equipment costs

- Staffing flexibility based on demand

However, compliance expectations remain just as strict.

How to start a care agency UK: what changes

When learning how to start a care agency UK, focus on these areas early:

- Recruitment and retention of carers

- Scheduling and travel time management

- Lone-worker safety

- Accurate care records across multiple locations

- Strong supervision and spot-check systems

Domiciliary care agencies often fail because growth outpaces control. Inspectors look closely at how you monitor care delivered off-site.

Domiciliary care agency business plan: what to include

A strong domiciliary care agency business plan differs from a care home plan in a few key ways:

- Staffing capacity linked to care hours, not beds

- Travel time and rota efficiency

- Referral sources (local authorities, private clients, NHS)

- Clear pricing per visit or per hour

- Systems for supervising staff in the field

Cashflow depends on care hours delivered, so accuracy matters.

Running a care agency: what breaks first

When running a care agency, problems usually appear in three places:

- Missed or late visits due to poor rota planning

- Inadequate supervision of carers working alone

- Inconsistent care records that don’t reflect real visits

Strong agencies fix these early with:

- Digital scheduling

- Regular supervision

- Clear escalation procedures

Care home vs care agency: a quick decision rule

If you want faster setup and lower risk, a care agency often makes sense first. If you want long-term asset value and can manage higher costs, a care home may suit you better.

Choose the model you can control safely, not the one that sounds more impressive.

Conclusion

Starting a care home in the UK is beyond a business decision, it’s a long-term responsibility. The providers that succeed don’t rush the process or rely on assumptions. They choose the right care model, design their service around regulatory expectations, control risk early, and build systems that hold up under inspection, commissioning scrutiny, and growth.

Whether you’re opening a residential care home or deciding that a domiciliary care agency is the better first step, the same principle applies: compliance comes first, sustainability comes next, and growth follows good governance, not the other way around.

Need expert support to strengthen your care service’s readiness?

Running a care service means operating under constant scrutiny. Even providers delivering good care can struggle with unclear accountability, documentation that doesn’t match day-to-day practice, or expansion that outpaces governance.

Care Sync Experts supports care homes and domiciliary care agencies across England, Wales, and Northern Ireland to build strong foundations before problems escalate. Support typically covers:

- Regulatory readiness and registration support

- Policy and governance alignment

- Inspection and commissioning preparation

- Sustainable growth planning

- Ongoing compliance and advisory support

Book a free readiness consultation

If you’re unsure whether your systems would stand up to inspection, commissioning review, or planned expansion, a short conversation now can prevent costly disruption later.

This article reflects UK care regulation and sector practice as at 2026. Requirements may change, and providers should always refer to current guidance from the relevant regulator.

FAQ

Is a care home business profitable in the UK?

A care home can be profitable, but margins depend on occupancy, staffing control, and funding mix. Well-run homes with stable occupancy often achieve single-digit to low-teens net margins, not the high margins people assume.

Profitability improves when the home maintains consistent referrals, controls agency staffing costs, and avoids compliance failures that trigger enforcement or closures. Poor management, not lack of demand, is the main reason care homes struggle financially.

How much does a care home cost in the UK?

The cost of starting a care home in the UK varies widely. Property alone can range from hundreds of thousands to several million pounds, depending on size and location.

Beyond the building, owners must budget for staffing, equipment, compliance systems, insurance, and working capital to cover low occupancy in the early months. Most failures happen when owners underestimate cashflow needs, not the headline purchase price.

How do care agencies get clients in the UK?

Care agencies typically get clients through local authority commissioning, NHS referrals, private self-funding clients, and word-of-mouth. Many councils use frameworks or Dynamic Purchasing Systems (DPS), meaning agencies must apply and meet quality thresholds before receiving referrals.

Private clients often come through online visibility, hospital discharge teams, and community networks. Agencies that combine public contracts with private clients tend to be more stable.

How much do care agencies charge per hour in the UK?

Hourly rates for home care agencies in the UK vary by region and funding source. Local authority rates are usually lower, while private client rates are higher to reflect travel time, staffing costs, and compliance overheads.

Rates also depend on the level of care required, time of day, and visit length. Agencies that price too low often struggle to retain staff and maintain quality, which quickly leads to regulatory issues.

Would you like to receive update from CareSync Experts?